Georgian Strategic Analysis Center (GSAC) is launching work on energy security issues

Energy security is an essential component of state security. In turn, to ensure energy security, it is necessary to solve operational problems, as well as to develop a medium and long-term strategy and related tactical action plans. In this regard, some useful material is posted on the website of the Ministry of Economy and Sustainable Development of Georgia (it encompasses the responsibility for the operational activities and development of the energy sector; the effectiveness of such an institutional arrangement is a matter of separate discussion): Energy policy goal and main directions, National Energy Efficiency Action Plan, National Renewable Energy Action Plan, Electricity Supply Security Report. Given the importance of the topic to consolidate the sustainability of Georgian statehood, it is necessary to continue fundamental scientific research, which should answer the key questions: what does energy security mean for Georgia and what strategy can be used to achieve it?

In today’s global world energy trade exceeds trillions of dollars annually. Under these circumstances, discussing the energy independence of countries, both importers and exporters, is not relevant any more. They all depend on the international market. For example, in 2019, 40% of the revenues of the Russian federal budget (about 7.5 trillion rubles)[1] were generated at the expense of oil and gas, predominantly through export operations. Consequently, Russia is more dependent on the export of energy resources to the international and specifically the European market than importers are dependent on the purchase of Russian energy resources. This tendency, i.e. the importance of effective participation in the system of international energy cooperation is also well manifested in the example of Georgia, especially since we are an open, liberal economy country. Accordingly, our energy security depends on three main components:

A) Proper and efficient utilization of its energy potential;

B) Establishment of a rational structure of energy consumption, including electricity;

C) Full-fledged participation in the network of international energy cooperation.

Of course, an integral part of the problem and the most dangerous component is the Russian factor, which continues to occupy the territories of Georgia and, if necessary, will not hesitate to use the levers of energy policy to achieve its own political goals, which has been done more than once and not only against our country. Nord Stream 2 is a clear manifestation of such a policy.In the modern world, access to cheap energy resources is a cornerstone of the state’s economic development. According to existing studies, energy consumption will increase 1.4 times in 2010-2040 and amount to the equivalent of 18 billion tons of oil.[2] This fact should be especially noticeable for countries that have scarce reserves of natural energy. Georgia is one of these countries; the elaboration of the right energy policy for the future development of its economy is a vital factor.Therefore, due to the dramatic significance of the issue, representatives of state structures, non-governmental organizations and scientific research centers should be involved in its development. It is necessary for them to work in tune; these activities to serve ultimately one purpose – the development and implementation of the well-designed and effective energy policy of Georgia.

In the light of abovementioned, Georgian Strategic Analysis Center, a non-governmental organization, launched a working group on energy security, which aims to study the energy environment of Georgia and estimate the challenges and threats we may face, in the near future, as well as the medium and long-term perspective.

It is noteworthy that, on May 7 of this year, Georgian Strategic Analysis Center hosted the first roundtable discussion on the topic, which is subject of interest for all actors in the field of energy and, with a few exceptions, reflects the public consensus: “Georgia’s energy security and Russian interests.” Researchers of Georgian Strategic Analysis Center and energy security experts attended the meeting. The participants of the meeting discussed the current situation in the energy sector of Georgia, development prospects and challenges, as well as possible threats coming from Russia. Among the main threats, matter of special interest was covert involvement of Russian capital in the implementation of power generation and transmission capacity projects, as well as possible dependence on electricity imports from Russia. This was the first attempt by the Energy Security Team of Georgian Strategic Analysis Center to open a wide-ranging discussion, identify risks in the sector, as well as to draw appropriate conclusions and recommendations.

We are convinced that only broad public involvement, transparency and a free space for exchange of ideas will provide an opportunity to overcome the problems and challenges facing Georgian energy. This also represents the best way to avoid corruption risks. Our center is ready to cooperate with all stakeholders. On this platform, anyone will have the opportunity to justify their approaches, prove points and ask questions. Confrontation should stay in past; dealing with such a fundamental problem is possible only by listening carefully to the views of opponents, ensuring the traditions of high-level cultural dialogue based on European values and criteria for cooperation.

Such meetings, with the wide involvement of non-governmental and public structures, representatives of stakeholders, will undoubtedly help the country in the process of setting the right energy policy priorities and will become a serious contributing factor to the country’s energy security.

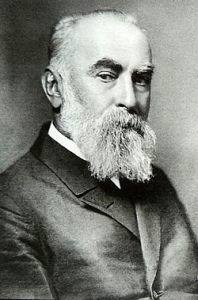

We will start working on the project by studying the historical part of Georgia’s energy sector, by publishing relevant studies, organizing round tables and conferences. First conference will be dedicated to the important contribution of great Georgian public official, Niko Nikoladze, to the development of Georgia’s energy sector development; the event will take place in GSAC in the beginning of September.

[1] https://1prime.ru/state_regulation/20190919/830338839.html

[2] https://www.eriras.ru/files/perspektivy-mirovoj-energetiki-do-2040.pdf

History of Georgian Energy: Part I

The history of Georgian energy spans for more than 150 years. It is noteworthy that the introduction of electricity in the country is connected with the great patriots of Georgia. In particular, such prominent public figures as Ilia Chavchavadze and Niko Nikoladze, with their visions and ideas, literally went ahead of time and laid the foundation for the beginning of electrification in Georgia.

The development of energy in Georgia dates back to the 1880s. Niko Nikoladze, a prominent public figure and economist, submitted a proposal to the city council on November 20, 1884, according to which the lighting of Tbilisi streets should have been provided with natural gas or electricity instead of kerosene lamps. However, the council could not decide for a long time which means to use to illuminate the capital. Consequently, until 1903, the streets of Tbilisi were still lit with kerosene lamps. In addition, Niko Nikoladze also applied to hand over the library to the city; all these proposals were rejected by the City Council on the grounds that “Mr. Nikoladze’s proposal is an aristocratic initiative, as it is only a matter of meeting personal needs” (citation and information retrieved from the historical archives of the Ministry of Justice; Foundation: 192 Description: 4 Document: 53).

The first power plant in Georgia was established in 1887 and was used to illuminate the Georgian Drama Theater in Tbilisi. Thermal engines were installed to generate electricity. The works were carried out by the Swedish company “Blanche”. One of the main initiators and inspirers of this case was the great Georgian writer and public figure Ilia Chavchavadze.

During this period, the electrification process was not limited to Tbilisi, it covered other regions of Georgia as well. In 1897, by order of Mikhail Romanov, the son of Russian Emperor Nicholas I, the head and director of the Borjomi Mineral Water Chemical Laboratory – Moldenhauer was assigned to solve the problem of supplying electricity to the Likani Palace.

The lighting of the Romanov Palace is connected with the launch of the first hydroelectric power plant in Georgia, the construction of which was carried out in 1898 in the Borjomi gorge. The initiator of the construction was the above-mentioned Moldenhauer. This hydropower plant could generate 103 kilowatts of electricity, the capacity of which fully met the requirements of the customer at that time. As mentioned, this was the first hydroelectric power plant operating in Georgia at that time, and it, together with the heat engines installed in Tbilisi, was the first step in the electrification of the country.

After that, the electrification process quickly spread to other districts of Tbilisi. For example, archival materials show that on March 3, 1899, Mr. Adelkhanov, the founder of the joint-stock company Adelkhanov & Company, petitioned the governor of Tbilisi for permission to electrify his factory on Vorontsov Street.

By September 28 the factory was equipped with an autonomous thermal power plant, during which the following equipment was used: “Archer” type heat engine and dynamo of “Tang” factory. The above-mentioned equipment was made in the UK, Birmingham. The dynamo was moving with the mentioned heating machine, which was making 250 turns per minute, thus producing 225 amps. (Material retrieved from the Historical Archive of the Ministry of Justice; Fund: 204 Archive Number: 4132).

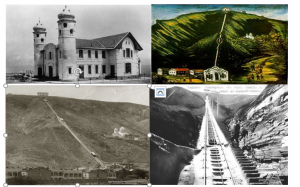

In July 1900, an unprecedented project was launched – the city government signed an agreement to build a funicular railway/cable line in Tbilisi and approved the Project, designed by engineer Robbie. The contract stipulated: to hand the funicular road over to the self-government after the completion of the construction, free travel for children under 5, mail carriers and the police-gendarmerie. “The Belgian anonymous society” would operate the funicular for 45 years, after which it would be transferred to the city free of charge. The agreement also envisaged the construction of an electric railway between Mtatsminda and Kojori, which, unfortunately, was not implemented.

Construction of the funicular began in September 1903, its design was mainly conducted by foreign specialists. The construction project was compiled by the French engineer A. Blanche, the architectural part was designed by Tbilisian architect A. Shimkevich. The construction of the road was supervised by Belgian and Italian engineers I. Ragoler and A.Fontana-Rossi. Niko Nikoladze also played great role in the implementation of the project: due to his contribution funicular ferroconcrete works for the overpass were completed.

The funicular opened on March 27, 1905, to which Niko Pirosmani dedicated a large painting. To encourage first-time travelers and walkers, „The Belgian anonymous society” has announced quite solid amount of money for those who would travel to and from Mtatsminda. (Material found on Wikipedia, Tbilisi Funicular Archive). Most likely, the electricity supply to the funicular was produced here as well by an autonomous thermal power plant,

a heat engine and dynamo were likely to be used. Our opinion on the above-mentioned issue is based only on the facts of how autonomous thermal power plants were arranged in such electrified institutions at that time, such as the Georgian Drama Theater in Tbilisi and the “Adelkhanov and Company” factory.

There are some interesting facts about the electrification of other regions of Georgia. For example, in 1914 the general plan for the construction of a power plant in the city of Sighnaghi was discussed by the governor of Tiflis (Sighnaghi was part of the Tiflis province at that time). The plan was reviewed and approved on May 23, 1914, and permission was granted to allocate all necessary funds to complete the construction of the power plant as soon as possible. (Material retrieved from the Historical Archive of the Ministry of Justice; Fund: 204 Archive Number: 4050).

It is noteworthy that studies conducted at the verge of the XIX-XX centuries found that water and water-related resources occupied leading position among the natural resources of Georgia; in this regard, the hydropower potential was particularly impressive. This was evidenced by the scientific calculations of that time. As then reported, according to the available water resources (rivers, lakes, reservoirs, glaciers, groundwater, swamps) Georgia was one of the leading countries in the world.

By the end of 1913, there were 7 small hydropower plants and several dozen thermal power plants in Georgia, with a total capacity of 9 MW and an annual output of almost 216 thousand kWh.

Since the 1920s, the construction of hydroelectric power plants in Georgia has become widespread: in 1927, the Avchala hydroelectric power plant “Zahesi” was built (installed capacity – 36.8 MW); 1928 – “Abhes”, in 1934 – “Rionhes”. By 1941, the total capacity of Georgian power plants was 180 MW. At the same time, the large-scale processing of coalfields in Georgia and the increase in demand for electricity have created a precondition for the construction of thermal power plants. In 1938, the first aggregates of the Tkvarcheli thermal power plant and the Tbilisi thermal power plant were launched.

A new stage of energy development has started in Georgia; although, thyis wiil be next component of our research.

Author: Lasha Bregvadze, Senior Fellow, Georgian Strategic Analysis Center

Before the establishment of the Soviet Union hydro energy resources of Georgia were not utilized at all. In 1913 there were only 70 small power plants isolated from each other in Georgia. In total they generated no more than 1000 horsepower; among them, the biggest was the Sokhumi hydropower plant with 400 kilowatts of power. Among fossil-fuel power stations, the most powerful was the Power plant of Tbilisi Tram, which worked on coal with approximately 2000 kilowatts of power. There were about 45 small fossil-fuel power stations in Tbilisi and many of them had only 10-15 horsepower. In 1913 the power of all power stations of Georgia in total was 8000 kilowatts. At that time literally, all plants were outdated and worn out. In 1913 was generated 20 million kilowatt-hours of energy. Of course, the negligible development of the Georgian energy industry was an indicator of a limited consumption of electrical energy. Georgian cities – Tbilisi, Kutaisi, Batumi, and Poti were in darkness. In 1913 annual generation of electrical energy per capita on average was 7,9 kilowatt-hours. Electricity as the stuff of luxury was accessible for the small part of the population only. (source: http://geworld.ge)

The first modern type hydropower plant was built on Mtkvari river, near Tbilisi city, in modern Mtskheta municipality, near the river mouth of Mtkvari and Aragvi. To meet the increased communal and industrial demand of Tbilisi, building a big hydropower station was under consideration even before the revolution of1917. There were several project proposals about on building hydro plant – primarily in the city, near the so called Madatov Island (1904-1905, a Belgian engineer Mettsem); on Aragvi river, near Tsitsamuri village (1907, engineers A. Andreev, N. Zvorikin); on Khrami river, near Arukhlo village (1920, engineers Avalishin, Kodjevnikov, Zvorikin, by the initiative of Alliance of Georgian Cities) and other. The project should have been implemented through foreign assistance. Since November of 1920 Ministry of Husbandry of the Democratic Republic of Georgia was preparing an agreement project on giving Swedish companies the right to utilize the energy of the Mtkvari and Aragvi rivers from Tsitsamuri to Upper Avtchala.

Despite the tough political and economic situation in the Soviet Union, then government managed to start activities on building of a big hydropower plant.

The Department of Hydropower of the Supreme Council of People’s Agriculture did field investigation, exploitation and started developing a project idea by engineer Melik-Pashaev. This project considered utilizing of Aragvi (from Bebri fortress to river mouth) and Mtkvari (from river mouth to railway bridge of Digomi) rivers.

In the first half of 1922, there was one more proposal regarding the building of a central fossil-fuel power plant with 10 000 horsepower directly in Tbilisi (engineer I. Vatsadze). The special export commission decided to give advantage to the building of hydro station in the abovementioned framework – on Mtkvari river, Upper Avtchala.

The building of ZaHes (ZaHes hydropower plant) had great significance for the recovery and development of the Georgian economy. On 23 May 1922 Tbilisi Council of Worker and Soldier Deputies decided to build a hydropower plant of 12 000 horsepower capacity near Upper Avtchala.

On 22 June 1922 Presidium of Tbilisi Council approved a draft on ZaHes building and established the ZaHes Committee.

ZaHes committee and construction managers did a great job to build a high-quality hydropower station in a very short time.

On 16 January 1923, the government adopted a decree according to which, in the first quarter of 1923 Tbilisi Council got 750 000 Rubles worth of gold to build ZaHes. In subsequent years, the USSR government permanently was assisting the construction financially.

After research of local water recourses, following the advice of Soviet and foreign specialists, as well as based on the findings of local Special Expert Commission, ZaHes power was determined in the range of 18 000 horsepower (instead of anticipated 10 000 horsepower). During the construction, its final capacity was upgraded to 36 000 horsepower.

Based on the ZaHes committee decision, electro-mechanic equipment was ordered to factories of Soviet Russia. These factories during the tough times of recovery needed support. Exception was made only regarding turbines – from 4 turbines one should have been constructed in Leningrad Metal factory, according to the “Fritsnomaier” design, remaining three – in “Fritsnomaier” factory (Germany).

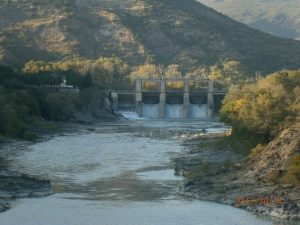

On 9 April 1927 started exploitation of the first cycle of the hydro power plant. It started working with full power in 1938, when 4 other turbines were added. Respectively, the total power of ZaHes was 36,8 000 kilowatts; annual generation of electro energy was 20,3 million kilowatt-hours on average. The construction consisted of a cement dam (height 34 m.), keeping water, a diversion canal (3 kilometers long), a delivery chamber, and the building of a hydro station. The dam created a round-the-clock regulation reservoir. The station itself played a vital role during World War II in providing transport and industry with electricity. In 1952 ZaHes was totally automated and mechanized. In this way, its power increased by 15% compared to the initial project proposal.

In 1923 a hydropower station with 1,1 thousand kilowatt power was constructed on the river Abasha. It started generating electricity in 1928. In the same year, another station with 16 000 kilowatt power was built on the Adjaristskali river. Because of geological drawbacks, its exploitation was postponed and started only in 1937.

Rioni Hydropower plant is located in Imereti region, Tchoma settlement, on both banks of the Rioni river. This station utilizes the energetic potential of the middle component of the Rioni river. In order to increase the water level, cement dam was built in Tchoma settlement. According to project design, water through diversion canal runs to Rioni hydro power station. Utilized water through special canal runs into Kvirila river.

The idea of the construction of the Rioni hydropower station is linked with the production of ferromanganese in Georgia. In 1924 was established a commission had to explore the capacities of both ferromanganese factory and hydropower station. In 1925 professor A. Liudin elaborated a hydropower plant project proposal, which considered the construction of 16,3 meters long dam on the Rioni river – with a breakwater and 1337 meters long derivation tunnel. Through this way, water runs into the Tskaltsitela river. The utilized drop was 42,5 m. and engineers planned to construct the equalizer reservoir at the end of the tunnel. The project envisaged 10 m3/water surface runoff. The nominal power of a small hydro plant was 9,0 megawatts, the total power of the hydroelectric site (including a small hydro station) was 29,43 megawatts. In 1926-27 engineer Melik-Pashaev designed a new project which was a modified variety of I. Liudin’s project. According to Melik-Pashaev’s project, the length of delivery increased to 9,0 kilometers, utilized drop – till 61,0 meters. As a result, the standing power of the hydro station became 48,0 megawatts. The construction of Rioni Hydropower plant started in 1927. The first hydroelectric component became operational in 1933, the whole station started was inaugurated in 1934. It should be pointed out, head buildings are located on the Rioni river, at the entrance of Kutaisi; a power unit – near the Kutaisi railway station. (source: file:///C:/Users/User/Downloads/სკრინინგის%20ანგარიში)

Only activation of the abovementioned hydro stations made it possible to rationally engage the power of hydro plants through creating a unified electro energetic system (“Sakenergo”). By 1945 seven electro stations ware consolidated in the Sakenergo system and energy was delivered to consumers through high voltage transmissions lines.

The market price of capital investments in the construction of electro stations and transmission lines in total was – 29,8 million Rubles (during recovery), 69,8 million Rubles (in the first 5 years), 229,9 million Rubles (next 5 years – increased by 229,3% compared to first 5 years); 123,6 million Rubles (during another 5 years). It should be said, one-fifth of capital investments of industry of the then republic was spent on construction of electro energy sector. That provided national economy with a powerful electro energetic market. Funds of electro energetic sector were increasing as well.

The market value of capital investments in the construction of electro stations and transmission lines in total (the price of “Sakenergo” primary funds only) was: 13, 8 million Rubles (in 1932); 125,7 million Rubles (in 1937); 191,3 million Rubles (in 9140), 277,9 million Rubles (in 1945), that is, during this very period it increased 19th fold. Small and medium-sized stations were primarily hydro power plants that was in accordance with the fossil-fuel structure of then republic. (source: http://geworld.ge)

Here we complete one of the most interesting periods of the Georgian energy industry history. In next part, which covers period after World war II, we will present our views on further development of the energy sector.

Author: Lasha Bregvadze, Senior Fellow, Georgian Strategic Analysis Center

The construction of hydropower plants in Soviet Georgia was associated with the development of socialism, or as soviet propaganda declared, communism, not scientific-technical progress. The builders of the hydropower plants were awarded Stalin-Lenin prizes and medals, promoted in career; poetry, poems, paintings, and cantatas were dedicated to power plants. This was the case with Zahesi, Rionhesi, Zhinvalihesi, Engurhesi and other HPPs, just before Khudoni. Khudoni HPP can be considered as the turning point of patriotic “Hesophilia”, the beginning of national “Hesophobia” and the first awakening of ecological thinking, which emerged with the national movement in the late 1980s. However, before we touch upon this rather painful and topical issue, which is still quite relevant to the population of Georgia nowadays, after more than 40 years, let us go through the history of building and designing major and vital hydropower plants such as Enguri and Zhinval HPPs, understand the progress and development of the country after their commissioning.  “Today, Enguri HPP, Zhinvali HPP, Vartsikhi HPP, Alazani irrigation system, cities are being built on our land and water, the previous small towns are looking like big cities … They are even going to build tunnels in the heart of the mountains … such a construction was planned that we could not have dreamed of in the past. ” – wrote the writer Nodar Tsuleiskiri in a newspaper report on the construction of the Enguri HPP in 1975; the only problem in the overall positive tone was the fear of demographic imbalance, complaining about the lack of disguised local staff: “Who should implement this big plan? We have to build our own house on our land (reference): https://www.radiotavisupleba.ge/a/%E1%83%A0%E1%83%9D%E1%83%92%E1%83%9D%E1%83%A0-%E1%83%98%E1%83%A7%E1%83%9D-%E1%83%AE%E1%83%A3%E1%83%93%E1%83%9D%E1%83%9C%E1%83%B0%E1%83%94%E1%83%A1%E1%83%98%E1%83%A1-%E1%83%A8%E1%83%94%E1%83%9B%E1%83%97%E1%83%AE%E1%83%95%E1%83%94%E1%83%95%E1%83%90%E1%83%A8%E1%83%98-/31199451.html)

“Today, Enguri HPP, Zhinvali HPP, Vartsikhi HPP, Alazani irrigation system, cities are being built on our land and water, the previous small towns are looking like big cities … They are even going to build tunnels in the heart of the mountains … such a construction was planned that we could not have dreamed of in the past. ” – wrote the writer Nodar Tsuleiskiri in a newspaper report on the construction of the Enguri HPP in 1975; the only problem in the overall positive tone was the fear of demographic imbalance, complaining about the lack of disguised local staff: “Who should implement this big plan? We have to build our own house on our land (reference): https://www.radiotavisupleba.ge/a/%E1%83%A0%E1%83%9D%E1%83%92%E1%83%9D%E1%83%A0-%E1%83%98%E1%83%A7%E1%83%9D-%E1%83%AE%E1%83%A3%E1%83%93%E1%83%9D%E1%83%9C%E1%83%B0%E1%83%94%E1%83%A1%E1%83%98%E1%83%A1-%E1%83%A8%E1%83%94%E1%83%9B%E1%83%97%E1%83%AE%E1%83%95%E1%83%94%E1%83%95%E1%83%90%E1%83%A8%E1%83%98-/31199451.html)

This is what the publications of Enguri HPP looked like, where the problems that have not lost their relevance for 40 years were still there.

The construction of the Enguri HPP was the implementation of the boldest idea in the history of Georgian technical thought. This idea involved the construction of the most complex unit of unique technical and engineering structures, which many specialists viewed with suspicion. Overcoming the greatest resistance became necessary to justify and approve the project. Skeptics considered this type of construction to be a fantastic idea and utopia. Optimists were alarmed by the scale of the construction and the complexity of the terrain, while proponents of the idea were frustrated by the grandeur of the vaulted dam and the seismic problem of the site.

In the first half of 1955, a complex expedition carried out hydropower and engineering-geological surveys of the natural conditions of the Enguri and its tributaries. A hydrogeological research expedition of 50 men walked the steep slopes of the Svaneti Mountains, the rocky banks of the Enguri and its tributaries. Their main goal was to carry out soil-climatic and geological-topographic works. Studies have shown that the heterogeneity of the terrain, the risk of seismic resistance, the diversity of soil, required a special, non-ordinary approach to the construction of the hydropower plant. The Enguri hydropower plant terrain is known to stretch for tens of square kilometers from Jvari to the Black Sea.

Georgian scientific and special design organizations did not have enough experience in designing and scientifically substantiating such buildings, which is why they spent a lot of time researching and studying a number of issues, namely: Study of the foundation of the arch dam – the strength of the rocky soil, the characteristics of shifts and filtration, the strengthening of the rocky soil through cementation; to determining the durability of the cementation curtain through tests; determining the shape, profile and tension condition of the arch dam through modeling and theoretical researches in the case of circular and non-circular outlines, when different types of loads are applied under construction and operation conditions; model examination of the dam in case of vibration when the dam is operating; high-pressure tunnel interior repairs, large-scale mining tensions, investigation of the shores of the Jvari and Gali Reservoirs and the sea shoreline in the Anaklia district in connection with the discharge of the Enguri into the Eristskali basin; study of the condition of concrete and selection of the composition of concrete for arched dams and other structures; the ground of the second stage of the cascade dam, unique hydraulic and electrical equipment, installations and other examinations.

The construction and commissioning of the Enguri HPP has improved not only Georgia’s electricity position, but also the irrigation of precious subtropical lands and the drying up of wetlands. Those lands with an area more than 17 thousand Ha, in the lower part of the Enguri and Eristskali and is used for growing tea, citrus and oily subtropical crops. Under the Jvari Reservoir were 11 small settlements, a total of 62 families (329 souls), collective farms and some state organizations. All these expenses were also reimbursed. In addition, the Enguri HPP frees 6,500 hectares of land from flood risk, which is also suitable for subtropical crops; At the same time, 6,000 families (25,000 souls) were given the opportunity to live in better conditions, whose relocation was otherwise necessary due to the floods.

In 1960, the project for the construction of the Enguri River Dam was newly developed in several options. Three principal schemes for the energy use of the Enguri River were discussed: By discharging the river (from its initial streams) into the river Eristskali; By discharging the Enguri River into the Eristskali River and using them jointly (in the middle of the Enguri River) and using the Enguri River’s own falls.

In the 1960 scheme, all pre-existing schemes were discussed in detail, and for the first time, exploration and survey work was carried out on all the responsible buildings of the next cascade. Taking into account all the economic and energy characteristics, the option of the cascade was selected, which provided for the discharge of the Enguri River into the Eristskali River basin. The main highlights of the Enguri River Cascade look as follows:

HPP Name | Dam height (m) | Power (M.G.V.T.) | Reservoir Volume (mlm3) |

Enguri | 271.5 | 2300 | 1110 |

Another important thermal power plant of the Georgian electricity industry was built in Tkvarcheli (450 km from Tbilisi). Construction began in 1933. The thermal power plant generated the first industrial electricity in 1938. It supplied electricity to the largest enterprises of the time – the Zestaponi Ferroalloy Plant and the Enguri Cellulose-Paper Mill. In 1938, the installed capacity of the thermal power plant was equal to 24 thousand KW. In 1956-1958 the power plant was expanded, as an outcome its capacity increased to 125 thousand kW. In 1977-1978 110 thousand KW power turbine was put into operation. Complete reconstruction of the enterprise was carried out in 1979-1983; As a result, the installed capacity of the power plant increased significantly. In 1938-1980, the thermal power plant generated more than 18 billion KW an hour of electricity and 1328 thousand Gcal of heat. Unfortunately, due to separatist movement in Abkhazia, Georgia the station has become an abandoned, empty building.

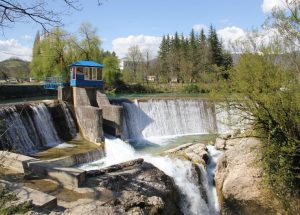

The next important hydropower plant built in Georgia is Zhinvali HPP. It was commissioned in 1985. The dam consists of 4 units, each of which has an average capacity of 32.5 thousand kW. At the time of commissioning, the average annual output of the dam was 390 million kW. It should be noted that certain inaccuracies occurred during the construction process, which later required modifications necessary. After the modified hydropower plant was put into operation, it generates an average of 400 million kW.

It should be noted, however, that due to the construction of the Zhinvali HPP, a large part of the village of Zhinvali was flooded and, consequently, a large part of the rural population was relocated to other areas. Mostly near the villages of Aranisi and Bichnigaurtkar, and a small part near village Chinti.

It should be noted that the primary purpose of creating the Zhinvali HPP water reservoir was to ensure its continuous function throughout the year. Notably, the water reservoir performs the function of regulating the river Aragvi in summer. It also provides partial water supply to the cities of Tbilisi and Mtskheta. Also, Tbilisi and Mtskheta have other sources of water supply.

Source: www.greens.ge/storage/publications/April2020/ofQtykWImm4ZutvsLF7c.pdf

This completes another important stage in the development of energy sector in Georgia. In the next part, we will talk about the projects implemented after the Second World War.

Author: Lasha Bregvadze, Senior Fellow, Georgian Strategic Analysis Center

Vartsikhe Hydropower Cascade is one of the most powerful seasonal hydropower complexes in Georgia. It is located in western Georgia, in Tskaltubo municipality, on the river Rioni. The total installed capacity of the station is 184 MW, electricity generation – 1 billion kWh; The cascade consists of 4 HPPs. The first HPP was became operational in 1976, the second in 1978, the third in 1980, and the fourth in 1988. The water of the Rioni River is used here on its lower end – from Rionhesi HPP canal to the confluence of the Gubistskali River. The drop of the river Rioni in this section is 64.5 meters.

Vartsikhe HPPs include a low-threshold dam built on the Rioni River in the village of Geguti (Tskaltubo Municipality) in 1976. The dam forms the Vartsikhe Reservoir, the length of the dam is 98 m, height – 21.2 m; The diversion route, which follows the right bank of the Rioni River (total length – 27.15 km), consists of 4 sections, at the end of each section there are hydropower plants included in the cascade. The projected installed capacity of each power plant of Vartsikhe HPP cascade is 46 MW, maximum pressure – 15 m, electricity generation – 250 million kWh. A separate HPP has two rotating blade turbines, each with a capacity of 23 MW. The generated electricity is supplied to the Georgian power system through 110 kV transmission lines.

On December 17, 1996, the joint stock company “Vartsikhe HPP Cascade” was established on the basis of the Vartsikhe Hydropower Cascade. According to the decision of the Government of Georgia, the HPP was privatized in 2005, in 2006 the Joint Stock Company was transformed into LLC and renamed “Vartsikhe-2005”. From January 1, 2007 it is included in the holding company “Georgian Manganese” Ltd.

Year | Electricity (Million kWh) |

1977 | 61,1 |

1980 | 360,6 |

1985 | 543,6 |

1990 | 851,4 |

1995 | 591,2 |

2000 | 665,7 |

2005 | 674,0 |

2010 | 796,2 |

2013 | 847,6 |

As it is known, in the 1980s of the XX century, the Georgian National Movement, in addition to bringing the charge of independence into the nation’s consciousness, was also driven by environmental issues. Defending the homeland, along with fighting for independence, also meant caring for its nature and cultural heritage. In this context, one of the most problematic subject was the Khudoni HPP construction project. The Greens of that time were protesting against the Khudoni HPP project; part of the station had already been built and its completion was advocated by the authorities of the Soviet Union, as well as Soviet Georgia, and much of the technical intelligentsia.

However, the project had a lot of flaws, which was revealed during its preliminary review and discussions. This was echoed in the then government of the Republic of Georgia. The resolution N11 of the Council of Ministers of the Georgian SSR issued on June 30, 1989, signed by Head of Government Nodar Chitanava, declared:

“Taking into account public opinion on the construction of Khudoni HPP, as well as the claims of the population of Mestia, Tsalenjikha, Zugdidi, Jvari and the society, the Council of Ministers of the Georgian SSR declares: The construction of Khudoni HPP should be stopped immediately and appropriate measures should be taken to completely eliminate the negative consequences caused by its construction.” However, the full calming of the uproar was already impossible. In fact, the dispute over the appropriateness of the construction of the Khudoni HPP between the conventional technocrats and the conventional ecologists has never stopped.

Khudoni HPP was portrayed by the Soviet authorities and mass media as another success of the national economy, which was planned many years ago and which comsumed many years and millions of Soviet rubles. The idea of building a 650 MW Khudoni HPP [dam height 200 m] was developed in the late 1960s at the Tbilisi Scientific Research Institute “Hydroproject”, and in 1972 the USSR State Planning Committee approved the project. Construction of the station began in 1985, and if it was not for the activism of the Greens and the National Movement, the Khudoni HPP first-line unit would have been commissioned in 1991. Out of the 464 million rubles allocated from the federal budget for the construction of the Khudoni HPP, 160 million rubles had already been spent by 1988.

The grand plan to develop the Enguri River was part of Soviet Georgia’s “industrial dream.” After the construction of the Enguri HPP and the Cascade of the Four Vardnili, the focus was on the upstream section. In addition to Khudoni HPP, it was also planned to build Vardnili (600-megawatt Tobarhes and 69-megawatt Nenskra cascade), but, as already mentioned, everything was stopped by Nodar Chitanava’s June 30, 1989 decree. Chitanava’s decision was considered by many to be a patriotic and courageous decision at that time. The so-called Technocrats thought differently: July 22, 1993 in the “Republic of Georgia” Member of the Georgian Academy of Engineering, Prof. Mikheil Ghoghoberidze wrote in the article “How much is Georgia worth?”: “The green movement all over the world was initially characterized by radicalism and populism, and naturally, the Georgian Greens could not go beyond this sense, but they went further and filled their handwriting with elements of blackmail … thus causing irreparable damage to the economy and society.”

Georgian specialists tried to calculate the losses and benefits caused by the shutdown of the Khudoni HPP project in 1989-1990. On January 11, 1990, “Young Communist” published essay “Georgia’s Energy Problems” offering readers the opinions of qualified experts without comments. Avtandil Gelenidze, a researcher at the Institute of Economic Planning and Management of the National Economy, wrote that the development of Georgia’s electricity sector had stopped in the 1980s. The construction of large energy facilities (Enguri HPP, Zhinvali HPP, IV stage of Vartsikhe HPP, new units of Tkvarcheli thermal power plant) could not lead to an increase in electricity production that would meet the needs. At that time, more than 50% of electricity consumption in Georgia came from industry, 25% from utility and household consumption, and the loss was 15%. HPPs accounted for 62% of all capacity. The prime cost of KWh of electricity generated by HPPs was 0.3 kopecks, and that of thermal power plants – 1.5 kopecks. Paata Tsintsadze, an employee of the Institute of Energy and Hydraulic Engineering: – “Georgia produces 14 billion kWh of electricity. We need 17-18 billion kWh. The deficit is 3-4 billion kWh. Georgia has 2,900 kWh per capita, or 60% of the average USSR rate. Only 12-15% of hydropower resources are used in Georgia. The share of small hydropower plants among them is 1%. The share of hydropower is 65%, thermal energy – 35%. “

Georgian government has returned to the issue of construction of Khudoni HPP since 2005. The company Trans Electrica Limited was to complete the construction of the station by 2018. For some reason it was considered that the protest of the 80s was only a struggle against communism and not an ecological activity. With such an approach, the suspended project of Namakhvani HPP was revived in parallel with the Enguri HPP, which was one of the favorite projects of the Union Institute of “Hydroproject” since the 70s of the last century. However, the resumption of the construction of Khudoni HPP and Namakhvani HPP was opposed by both the locals (their opinion is still mostly ignored) and environmental organizations, which, along with legal shortcomings, also indicate a lack of environmental thinking. Due to all the above, at this stage, as it is known, the construction of Khudoni HPP has been suspended for an indefinite period of time. The prospect of building Namakhvani HPP is also vague.

Shaori Hydroelectric Power Plant – an annual regulating hydroelectric power plant is located in Tkibuli Municipality, Tkibuli city. This is the first stage of the Shaor-Tkibuli HPP cascade. Water from the Shaori River is used at the station. The reservoir is formed by a dam built in the Shaori hollow, near the village of Khorga. The power knot is located in the city of Tkibuli. The station was put into operation in 1955. Its installed capacity is 39.2 MW and the projected average annual output is 139 GW. A diversion-type high-pressure HPP is regulated by a reservoir.

In May 1958, the federal government decided to build a power plant near Tbilisi. In July 1958, by the decision of the Council of Ministers of the Georgian SSR, a plot of land was allocated for the construction of a power plant in the Mtskheta region near Zahesi, but due to the expected environmental pollution of the capital city, the government changed its decision and in 1959 selected Rustavi (Gardabani district) to build the station.

Construction of “Tbilsres” began in 1960. The first three power units were put into operation in 1963-1965, with a total capacity of 450 (3 × 150) thousand KW, and in 1967–1972 another five blocks of 800 (5 × 160) thousand kW capacity were added to them. The commissioning of the thermal power plant was a new step in the development of Georgia’s electricity sector. Since it became operational into the previously established proportion between hydropower and thermal power plant capacity has dramatically changed. If in 1963 the share of thermal power plants in the total production of electricity was 36.9%, by 1970 it increased to 70.5%, and by 1975 it increased to 77.9%. The main share came from “Tbilsres”. In the history of its existence, “Tbilsres” has generated in 1977 the largest amount of electricity – 7763 million KWh.

Reconstruction/expansion of “Tbilsres” was carried out in 1990-1994. The installed capacity was 1100 MW. The 9th block (1991; The total installed capacity became 1100 MW) and 10th block (1994; full installed capacity 1700 MW) – new generation power units with supercritical parameters were put into operation, each with a capacity of 300 megawatts.

Power units №5, №6 and №7 were not repaired and, as a result, they became technically faulty. №7 power units went out of order in 1994, №5 power units in 1995, and №6 power units in 1996. As of January 1, 2002, the installed capacity of the station was 414 MW in the form of №3, №4 and №8 blocks. In 1998, the joint-stock company “Tbilsres” was established on the basis of the Tbilisi State District Power Plant. The state owned the full package of shares.

In 1999, with the appropriate infrastructure, the new units (№9 and №10) were transferred to company AES together with JSC “Telasi”. And by the order of the Ministry of State Property Management of Georgia №1-3-252 of April 26, 2002, №1 and №2 power units were written off in order to build a new one; that is why in 2003 the installed capacity of the station was 840 MW. At the same time, it was not possible to carry out repair and restoration works on the №5 and №7 power units that were forcibly stopped in 1994 – 1996. Due to lack of finances, neither №3, №4 and №8 of the power units underwent a complete overhaul. In total, five of the remaining eight blocks were fully out of order and three were relatively viable.

Unfortunately, our current reality shows that the problems and challenges are still there, moreover, they seem even more problematic in Georgia today. The questions remain unanswered – is it necessary to build giant hydropower plants in the country and if the answer is yes, why? If it is not necessary, all this should be still well argumented; however, up to now neither the government nor the nature protection organizations have done that. More attention should be paid to the sources of alternative energy (solar, wind, etc.); whether our country has respective potential, capacity, financial and human resources to implement such projects. These problems, together with disastrous consumer structure (for example, motivating bitcoin production) will inevitably trigger electricity shortages the country, resulting in necessity to buy large quantities of electricity from neighboring countries; in its turn, this will downgrade the level of country’s energy independence and security. At the same time, eventually these processes will dramatically increase the cost of electricity for the population.

Vartsikhe Hydropower Cascade is one of the most powerful seasonal hydropower complexes in Georgia. It is located in western Georgia, in Tskaltubo municipality, on the river Rioni. The total installed capacity of the station is 184 MW, electricity generation – 1 billion kWh; The cascade consists of 4 HPPs. The first HPP was became operational in 1976, the second in 1978, the third in 1980, and the fourth in 1988. The water of the Rioni River is used here on its lower end – from Rionhesi HPP canal to the confluence of the Gubistskali River. The drop of the river Rioni in this section is 64.5 meters.

Vartsikhe HPPs include a low-threshold dam built on the Rioni River in the village of Geguti (Tskaltubo Municipality) in 1976. The dam forms the Vartsikhe Reservoir, the length of the dam is 98 m, height – 21.2 m; The diversion route, which follows the right bank of the Rioni River (total length – 27.15 km), consists of 4 sections, at the end of each section there are hydropower plants included in the cascade. The projected installed capacity of each power plant of Vartsikhe HPP cascade is 46 MW, maximum pressure – 15 m, electricity generation – 250 million kWh. A separate HPP has two rotating blade turbines, each with a capacity of 23 MW. The generated electricity is supplied to the Georgian power system through 110 kV transmission lines.

On December 17, 1996, the joint stock company “Vartsikhe HPP Cascade” was established on the basis of the Vartsikhe Hydropower Cascade. According to the decision of the Government of Georgia, the HPP was privatized in 2005, in 2006 the Joint Stock Company was transformed into LLC and renamed “Vartsikhe-2005”. From January 1, 2007 it is included in the holding company “Georgian Manganese” Ltd.

Year | Electricity (Million kWh) |

1977 | 61,1 |

1980 | 360,6 |

1985 | 543,6 |

1990 | 851,4 |

1995 | 591,2 |

2000 | 665,7 |

2005 | 674,0 |

2010 | 796,2 |

2013 | 847,6 |

As it is known, in the 1980s of the XX century, the Georgian National Movement, in addition to bringing the charge of independence into the nation’s consciousness, was also driven by environmental issues. Defending the homeland, along with fighting for independence, also meant caring for its nature and cultural heritage. In this context, one of the most problematic subject was the Khudoni HPP construction project. The Greens of that time were protesting against the Khudoni HPP project; part of the station had already been built and its completion was advocated by the authorities of the Soviet Union, as well as Soviet Georgia, and much of the technical intelligentsia.

However, the project had a lot of flaws, which was revealed during its preliminary review and discussions. This was echoed in the then government of the Republic of Georgia. The resolution N11 of the Council of Ministers of the Georgian SSR issued on June 30, 1989, signed by Head of Government Nodar Chitanava, declared:

“Taking into account public opinion on the construction of Khudoni HPP, as well as the claims of the population of Mestia, Tsalenjikha, Zugdidi, Jvari and the society, the Council of Ministers of the Georgian SSR declares: The construction of Khudoni HPP should be stopped immediately and appropriate measures should be taken to completely eliminate the negative consequences caused by its construction.” However, the full calming of the uproar was already impossible. In fact, the dispute over the appropriateness of the construction of the Khudoni HPP between the conventional technocrats and the conventional ecologists has never stopped.

Khudoni HPP was portrayed by the Soviet authorities and mass media as another success of the national economy, which was planned many years ago and which comsumed many years and millions of Soviet rubles. The idea of building a 650 MW Khudoni HPP [dam height 200 m] was developed in the late 1960s at the Tbilisi Scientific Research Institute “Hydroproject”, and in 1972 the USSR State Planning Committee approved the project. Construction of the station began in 1985, and if it was not for the activism of the Greens and the National Movement, the Khudoni HPP first-line unit would have been commissioned in 1991. Out of the 464 million rubles allocated from the federal budget for the construction of the Khudoni HPP, 160 million rubles had already been spent by 1988.

The grand plan to develop the Enguri River was part of Soviet Georgia’s “industrial dream.” After the construction of the Enguri HPP and the Cascade of the Four Vardnili, the focus was on the upstream section. In addition to Khudoni HPP, it was also planned to build Vardnili (600-megawatt Tobarhes and 69-megawatt Nenskra cascade), but, as already mentioned, everything was stopped by Nodar Chitanava’s June 30, 1989 decree. Chitanava’s decision was considered by many to be a patriotic and courageous decision at that time. The so-called Technocrats thought differently: July 22, 1993 in the “Republic of Georgia” Member of the Georgian Academy of Engineering, Prof. Mikheil Ghoghoberidze wrote in the article “How much is Georgia worth?”: “The green movement all over the world was initially characterized by radicalism and populism, and naturally, the Georgian Greens could not go beyond this sense, but they went further and filled their handwriting with elements of blackmail … thus causing irreparable damage to the economy and society.”

Georgian specialists tried to calculate the losses and benefits caused by the shutdown of the Khudoni HPP project in 1989-1990. On January 11, 1990, “Young Communist” published essay “Georgia’s Energy Problems” offering readers the opinions of qualified experts without comments. Avtandil Gelenidze, a researcher at the Institute of Economic Planning and Management of the National Economy, wrote that the development of Georgia’s electricity sector had stopped in the 1980s. The construction of large energy facilities (Enguri HPP, Zhinvali HPP, IV stage of Vartsikhe HPP, new units of Tkvarcheli thermal power plant) could not lead to an increase in electricity production that would meet the needs. At that time, more than 50% of electricity consumption in Georgia came from industry, 25% from utility and household consumption, and the loss was 15%. HPPs accounted for 62% of all capacity. The prime cost of KWh of electricity generated by HPPs was 0.3 kopecks, and that of thermal power plants – 1.5 kopecks. Paata Tsintsadze, an employee of the Institute of Energy and Hydraulic Engineering: – “Georgia produces 14 billion kWh of electricity. We need 17-18 billion kWh. The deficit is 3-4 billion kWh. Georgia has 2,900 kWh per capita, or 60% of the average USSR rate. Only 12-15% of hydropower resources are used in Georgia. The share of small hydropower plants among them is 1%. The share of hydropower is 65%, thermal energy – 35%. “

Georgian government has returned to the issue of construction of Khudoni HPP since 2005. The company Trans Electrica Limited was to complete the construction of the station by 2018. For some reason it was considered that the protest of the 80s was only a struggle against communism and not an ecological activity. With such an approach, the suspended project of Namakhvani HPP was revived in parallel with the Enguri HPP, which was one of the favorite projects of the Union Institute of “Hydroproject” since the 70s of the last century. However, the resumption of the construction of Khudoni HPP and Namakhvani HPP was opposed by both the locals (their opinion is still mostly ignored) and environmental organizations, which, along with legal shortcomings, also indicate a lack of environmental thinking. Due to all the above, at this stage, as it is known, the construction of Khudoni HPP has been suspended for an indefinite period of time. The prospect of building Namakhvani HPP is also vague.

Shaori Hydroelectric Power Plant – an annual regulating hydroelectric power plant is located in Tkibuli Municipality, Tkibuli city. This is the first stage of the Shaor-Tkibuli HPP cascade. Water from the Shaori River is used at the station. The reservoir is formed by a dam built in the Shaori hollow, near the village of Khorga. The power knot is located in the city of Tkibuli. The station was put into operation in 1955. Its installed capacity is 39.2 MW and the projected average annual output is 139 GW. A diversion-type high-pressure HPP is regulated by a reservoir.

In May 1958, the federal government decided to build a power plant near Tbilisi. In July 1958, by the decision of the Council of Ministers of the Georgian SSR, a plot of land was allocated for the construction of a power plant in the Mtskheta region near Zahesi, but due to the expected environmental pollution of the capital city, the government changed its decision and in 1959 selected Rustavi (Gardabani district) to build the station.

Construction of “Tbilsres” began in 1960. The first three power units were put into operation in 1963-1965, with a total capacity of 450 (3 × 150) thousand KW, and in 1967–1972 another five blocks of 800 (5 × 160) thousand kW capacity were added to them. The commissioning of the thermal power plant was a new step in the development of Georgia’s electricity sector. Since it became operational into the previously established proportion between hydropower and thermal power plant capacity has dramatically changed. If in 1963 the share of thermal power plants in the total production of electricity was 36.9%, by 1970 it increased to 70.5%, and by 1975 it increased to 77.9%. The main share came from “Tbilsres”. In the history of its existence, “Tbilsres” has generated in 1977 the largest amount of electricity – 7763 million KWh.

Reconstruction/expansion of “Tbilsres” was carried out in 1990-1994. The installed capacity was 1100 MW. The 9th block (1991; The total installed capacity became 1100 MW) and 10th block (1994; full installed capacity 1700 MW) – new generation power units with supercritical parameters were put into operation, each with a capacity of 300 megawatts.

Power units №5, №6 and №7 were not repaired and, as a result, they became technically faulty. №7 power units went out of order in 1994, №5 power units in 1995, and №6 power units in 1996. As of January 1, 2002, the installed capacity of the station was 414 MW in the form of №3, №4 and №8 blocks. In 1998, the joint-stock company “Tbilsres” was established on the basis of the Tbilisi State District Power Plant. The state owned the full package of shares.

In 1999, with the appropriate infrastructure, the new units (№9 and №10) were transferred to company AES together with JSC “Telasi”. And by the order of the Ministry of State Property Management of Georgia №1-3-252 of April 26, 2002, №1 and №2 power units were written off in order to build a new one; that is why in 2003 the installed capacity of the station was 840 MW. At the same time, it was not possible to carry out repair and restoration works on the №5 and №7 power units that were forcibly stopped in 1994 – 1996. Due to lack of finances, neither №3, №4 and №8 of the power units underwent a complete overhaul. In total, five of the remaining eight blocks were fully out of order and three were relatively viable.

Unfortunately, our current reality shows that the problems and challenges are still there, moreover, they seem even more problematic in Georgia today. The questions remain unanswered – is it necessary to build giant hydropower plants in the country and if the answer is yes, why? If it is not necessary, all this should be still well argumented; however, up to now neither the government nor the nature protection organizations have done that. More attention should be paid to the sources of alternative energy (solar, wind, etc.); whether our country has respective potential, capacity, financial and human resources to implement such projects. These problems, together with disastrous consumer structure (for example, motivating bitcoin production) will inevitably trigger electricity shortages the country, resulting in necessity to buy large quantities of electricity from neighboring countries; in its turn, this will downgrade the level of country’s energy independence and security. At the same time, eventually these processes will dramatically increase the cost of electricity for the population.

Author: Lasha Bregvadze, Senior Fellow, Georgian Strategic Analysis Center